POI Risk Assessment Tool

Your POI Risk Assessment

After surgery, many patients expect to feel sore-but not stuck. One of the most common, frustrating, and preventable complications is postoperative ileus (POI): when your gut just stops working. You can’t eat, you’re bloated, you haven’t passed gas or had a bowel movement in days, and your pain meds might be the reason why. This isn’t just discomfort-it adds days to your hospital stay, increases costs, and delays recovery. The link between opioids and POI is clear, strong, and well-documented. But here’s the good news: we now know how to stop it before it starts.

What Exactly Is Postoperative Ileus?

Postoperative ileus isn’t a bowel obstruction. It’s a temporary paralysis of the intestines triggered by surgery, stress, and yes-opioids. After an operation, your gut’s natural rhythm slows or stops. Food doesn’t move. Gas doesn’t pass. You feel full, nauseous, and distended. Symptoms usually show up within 24 to 72 hours after surgery. If nothing moves by day three, it’s considered clinically significant. The average patient with POI spends two to three extra days in the hospital. In the U.S. alone, this adds up to $1.6 billion a year in extra costs.

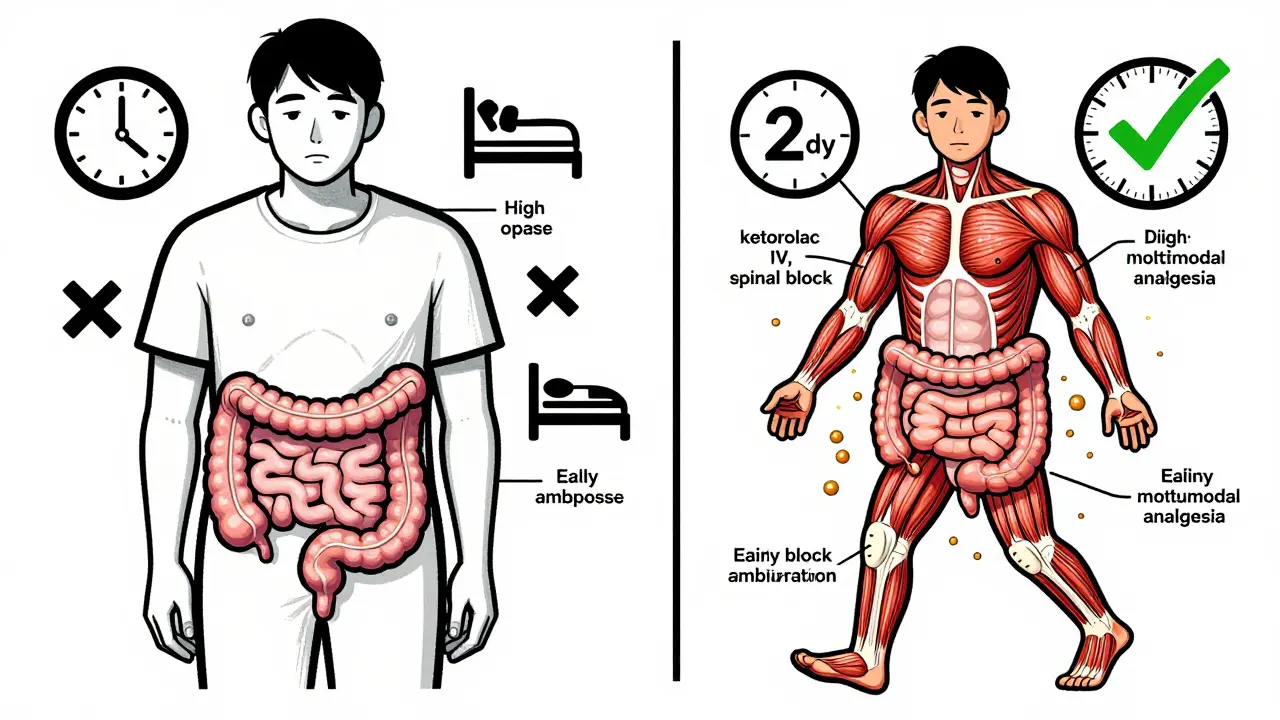

It’s not just about pain meds. Surgery itself causes inflammation, nerve disruption, and stress hormones that slow digestion. But opioids? They’re the biggest accelerator. They bind to mu-opioid receptors in your gut lining, turning off the muscles that push food along. Studies show opioids can cut colonic motility by up to 70%. That’s why patients on high-dose opioids often take five or more days to have their first bowel movement-compared to two days for those on lower doses.

How Opioids Slow Down Your Gut

Opioids don’t just numb pain in your brain-they also hit your intestines like a switch-off button. When you get morphine, fentanyl, or oxycodone after surgery, those drugs bind to receptors in the myenteric plexus-the network of nerves that controls gut movement. This causes three things to happen:

- Reduced contractions in your stomach and small intestine

- Slowed transit time-food takes 50% to 200% longer to move through

- Increased water absorption, leading to hard, dry stools

The numbers are telling: patients receiving 5-10 mg of morphine equivalents per hour show delayed gastric emptying and sluggish small bowel movement. Over 46% of opioid users report hard stools. Nearly 60% strain during bowel movements. Bloating? That’s in 40-61% of cases. These aren’t rare side effects-they’re predictable outcomes of standard opioid dosing.

And it gets worse. The body releases its own opioids during surgery. So even if you’re not on pain meds, your body is helping slow your gut. Combine that with opioids, and you’ve got a perfect storm.

Traditional Treatments Don’t Work Well

For decades, the go-to fix for POI was the nasogastric tube. Insert a tube through your nose into your stomach to suck out fluid and gas. It sounds drastic-and it is. Studies show it reduces POI duration by only 12%. That’s barely better than doing nothing. Other outdated methods like IV fluids, bed rest, or waiting it out just prolong suffering.

Nausea and vomiting are common, so anti-nausea drugs are often given. But they don’t fix the root cause. You might feel less sick, but your gut still isn’t moving. That’s why simply managing symptoms isn’t enough. You need to target the mechanism: opioid-induced gut paralysis.

Prevention: The Real Game-Changer

The best way to handle POI? Don’t let it happen in the first place. The most effective strategy is multimodal analgesia-using non-opioid pain relief as the foundation, and opioids only as a backup.

Here’s what works:

- Acetaminophen (IV or oral): Given every 6 hours. It’s safe, effective, and doesn’t slow the gut.

- Ketorolac (IV): A non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID). Reduces inflammation and pain without opioids. Not for everyone (avoid if kidney issues or bleeding risk), but great for many.

- Regional anesthesia: Spinal or epidural blocks cut opioid needs by 50% or more. Orthopedic patients using spinal anesthesia had POI rates of just 8.5% vs. 22.3% with general anesthesia and opioids.

- Limit total opioid dose: Keep total morphine equivalents under 30 mg in the first 24 hours. Studies show this drops POI incidence from 30% to 18%.

One hospital in Michigan tracked their results after switching protocols. They went from an average POI duration of 4.1 days to 2.7 days. That’s a 34% improvement. And it didn’t require fancy drugs-just better pain management.

Peripheral Opioid Antagonists: The Targeted Fix

What if you still need opioids for pain? That’s where peripheral opioid receptor antagonists come in. These drugs block opioids in your gut-without touching pain relief in your brain.

Two are approved for this:

- Alvimopan: Taken orally. Shown to reduce time to bowel recovery by 18-24 hours after abdominal surgery.

- Methylnaltrexone (Relistor®): Given as a subcutaneous injection. Works in opioid-tolerant patients and cuts recovery time by 30-40%.

These aren’t magic bullets. They’re expensive-methylnaltrexone costs about $147.50 per dose. But in high-risk patients (abdominal surgery, opioid-naive), the benefit outweighs the cost. The Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society now recommends them routinely for these groups.

Important warning: Don’t use them if you have a known bowel obstruction. That’s rare, but serious. They’re designed for functional paralysis-not mechanical blockage.

Simple, Low-Cost Strategies That Work

You don’t always need drugs. Some of the most effective tools are free:

- Early ambulation: Get up and walk within 4 hours after surgery. One study found this cuts POI duration by 22 hours. Even short walks help.

- Chewing gum: Yes, really. Chewing tricks your brain into thinking you’re eating. It stimulates saliva, digestive enzymes, and gut motility. Nurses on AllNurses.com reported success with patients chewing gum four times a day. It reduced POI duration from 4.1 to 2.7 days.

- Early oral intake: Don’t wait for “bowel sounds.” If you’re not vomiting, offer sips of water or clear fluids within 6-8 hours after surgery. Eating early reactivates the gut.

These aren’t fringe ideas-they’re backed by clinical trials and now part of ERAS guidelines. And they’re easy to implement.

What Doesn’t Work (and Why)

Some old habits die hard-and they hurt patients:

- Waiting for bowel sounds: Doctors used to listen for gurgles before letting patients eat. But studies show bowel sounds don’t predict when the gut will move. You can have loud gurgles and still be ileic. Skip this.

- Delayed mobilization: Keeping patients in bed “for rest” is outdated. Movement is medicine.

- High-dose opioids as default: Giving 50+ morphine equivalents in 48 hours? That’s a recipe for 5+ days of ileus. One survey found patients on that dose took 2.7 times longer to have their first bowel movement.

Resistance to change is real. In 63% of hospitals, anesthesia teams initially pushed back when non-opioid protocols were introduced. Nurses didn’t know how to encourage early walking. But once training happened, compliance jumped. One program hit 90% adherence within a year.

Who’s at Highest Risk?

Not everyone gets POI equally. Risk factors include:

- Abdominal surgery (especially bowel or pelvic)

- Older age

- Longer surgery time

- Opioid-naive patients (those not used to opioids before)

- High opioid doses (>40 morphine equivalents in 24 hours)

Colorectal surgery programs have POI prevention protocols in 78% of cases. Orthopedic programs? Only 34%. That’s a gap. Hip and knee patients aren’t immune. In fact, one study found that switching from general anesthesia with opioids to spinal anesthesia with multimodal pain control cut POI rates in half.

The Cost of Doing Nothing

POI isn’t just a medical issue-it’s a financial one. Hospitals get penalized if patients get readmitted for complications. In 2022, 15.7% of general surgery programs in the U.S. were hit with CMS penalties averaging $187,000 each. That’s why top hospitals now track POI like a vital sign: time to first flatus, time to first bowel movement, and ability to tolerate 1,000 mL of oral fluid within 24 hours of symptom onset.

Programs with full ERAS protocols save $2,300 per patient. That’s not just money-it’s bed space, staff time, and faster recovery for the next patient.

What’s Coming Next?

Research is moving fast. A reformulated version of alvimopan is in late-stage trials. Fecal microbiome transplants are being tested for stubborn POI cases. AI models are being trained to predict who’s at risk based on 27 pre-op factors-with 86% accuracy. These won’t replace proven methods, but they’ll help target care where it’s needed most.

By 2027, comprehensive POI prevention is expected to become standard. Right now, academic hospitals lead the way. Rural facilities? Only 28% have formal protocols. That’s a gap in care that needs closing.

Bottom Line

Postoperative ileus isn’t inevitable. It’s preventable. Opioids are a major driver-but they’re not the only one. The solution isn’t to stop opioids entirely-it’s to use them smarter. Combine low-dose opioids with non-opioid pain relief, get patients moving early, and consider a peripheral antagonist if you’re high-risk. Simple, evidence-based steps cut recovery time, reduce costs, and make surgery less miserable. You don’t need a miracle. You just need a plan.

How long does postoperative ileus usually last?

Without intervention, POI typically lasts 3 to 5 days. With proper prevention-like multimodal analgesia and early mobility-it can be reduced to under 2 days. If nothing moves by day 3, it’s considered clinically significant and requires active management.

Can I still get pain relief without opioids?

Yes. Acetaminophen (Tylenol), ketorolac (Toradol), and regional anesthesia (like epidurals or spinal blocks) are highly effective for surgical pain and don’t slow your gut. Many patients find these enough on their own. Opioids are reserved for breakthrough pain, not first-line.

Why is chewing gum recommended after surgery?

Chewing gum tricks your brain into thinking you’re eating. That triggers the cephalic phase of digestion-saliva production, stomach acid release, and gut motility. Studies show chewing gum four times a day can reduce POI duration by nearly 1.5 days. It’s cheap, safe, and easy to do.

Are peripheral opioid antagonists safe?

Yes, for most patients. Drugs like methylnaltrexone and alvimopan block opioid receptors only in the gut, not the brain. So pain relief stays intact. But they’re contraindicated if you have a bowel obstruction, which occurs in less than 0.5% of surgical patients. Always check with your care team before use.

What if I’m already on opioids before surgery?

Chronic opioid users are at higher risk for severe POI. Their gut is already adapted to opioids, so the extra dose after surgery hits harder. Prevention here means using multimodal analgesia even more aggressively and considering a peripheral antagonist early. Don’t stop opioids abruptly-this can cause withdrawal, which also delays recovery.

9 Comments

Mike HammerFebruary 14, 2026 AT 03:58

man i had this after my appendix thing last year. thought i was dying. no gas for like 5 days. doc just said "wait it out" like i was a plant. then i started chewing gum like a maniac and walking to the bathroom every hour. weirdly worked. no opioids either. just tylenol and vibes.

Daniel DoverFebruary 14, 2026 AT 13:43

Early ambulation is non-negotiable. Simple as that.

Charlotte DacreFebruary 15, 2026 AT 00:19

so let me get this straight. we have a $1.6 billion problem because hospitals still treat patients like they’re in a medieval monastery? "hold the water, wait for the gurgles, and here’s your morphine drip, enjoy your 5-day prison stay."

chewing gum is cheaper than a coffee and works better than half the meds they throw at you. why is this even a debate?

Chiruvella Pardha KrishnaFebruary 15, 2026 AT 13:32

the human body is a symphony of invisible forces. when we introduce external chemical agents-opioids, for instance-we disrupt the delicate harmonic balance of the enteric nervous system. it is not merely a pharmacological event, but an ontological rupture in the natural rhythm of life itself.

modern medicine, obsessed with quantification, forgets that the gut has memory. it remembers trauma. it remembers silence. it remembers the absence of movement. to treat ileus is not to administer drugs, but to restore the soul’s whisper to the intestines.

walking, chewing, sipping water-these are not interventions. they are rituals of reconnection.

Virginia KimballFebruary 16, 2026 AT 21:01

chewing gum after surgery is the most underrated hack ever. i was skeptical too-until i did it. felt like a kid again, just chewing and waiting for my body to catch up. my nurse laughed but didn’t stop me. by day 2? i was eating soup like a champ.

also, no one talks about how scary it feels when your body just... stops. like your insides are on vacation and forgot to tell you. so yeah, move, chew, sip, and scream into a pillow if you need to. you’re not broken. your gut just needs a pep talk.

Kapil VermaFebruary 18, 2026 AT 15:11

in india we don’t need fancy drugs. we just walk. we eat roti the same day. no hospital in my village gives opioids unless you’re dying. and guess what? no one gets ileus. you think this is a medical problem? no. it’s a western overmedication crisis.

your doctors are addicted to prescriptions. they forgot that movement is medicine. your body doesn’t need a pill for every breath. it needs a walk. that’s it.

Michael PageFebruary 20, 2026 AT 07:17

the fact that we’re still debating whether chewing gum helps is a reflection of how deeply entrenched outdated protocols are. the data is clear, but implementation lags because change requires coordination, not just evidence.

it’s not about the science anymore. it’s about systems. and systems resist change unless they’re forced to.

Sarah BarrettFebruary 21, 2026 AT 17:19

While the data supporting multimodal analgesia and early ambulation is compelling, I find it concerning that peripheral opioid antagonists are still considered niche despite their efficacy. The cost barrier is real, but when weighed against extended hospital stays, the ROI is undeniable.

There’s also a psychological component: patients who feel actively involved in their recovery-through chewing, walking, or even just being encouraged to drink water-report significantly lower anxiety levels. This isn’t just physiology. It’s dignity.

Erica Banatao DarilagFebruary 22, 2026 AT 19:27

i just had my mom go through this last month. they gave her 60mg of morphine in 24 hours. she was bloated for 6 days. no one mentioned gum. no one said walk. just "wait and see."

we’re not doing this right. i’m so glad this post exists. maybe now more nurses will read it.