When a generic drug hits the market, you might assume it’s just a cheaper copy. But how do regulators know it works the same way as the brand-name version? The answer lies in two numbers: Cmax and AUC. These aren’t just lab terms-they’re the backbone of bioequivalence, the system that ensures generic drugs are just as safe and effective as their branded counterparts.

What Cmax Tells You About Drug Absorption

Cmax stands for maximum plasma concentration. It’s the highest level a drug reaches in your bloodstream after you take it. Think of it like the peak of a mountain on a graph. If you take a painkiller, Cmax tells you how high the drug spikes in your blood-and when that spike happens (called Tmax).

For some drugs, that peak matters a lot. Take ibuprofen: if the Cmax is too low, you won’t feel pain relief fast enough. If it’s too high, you might get stomach upset or even kidney strain. That’s why regulators don’t just look at whether the drug gets into your system-they check how fast and how high it climbs.

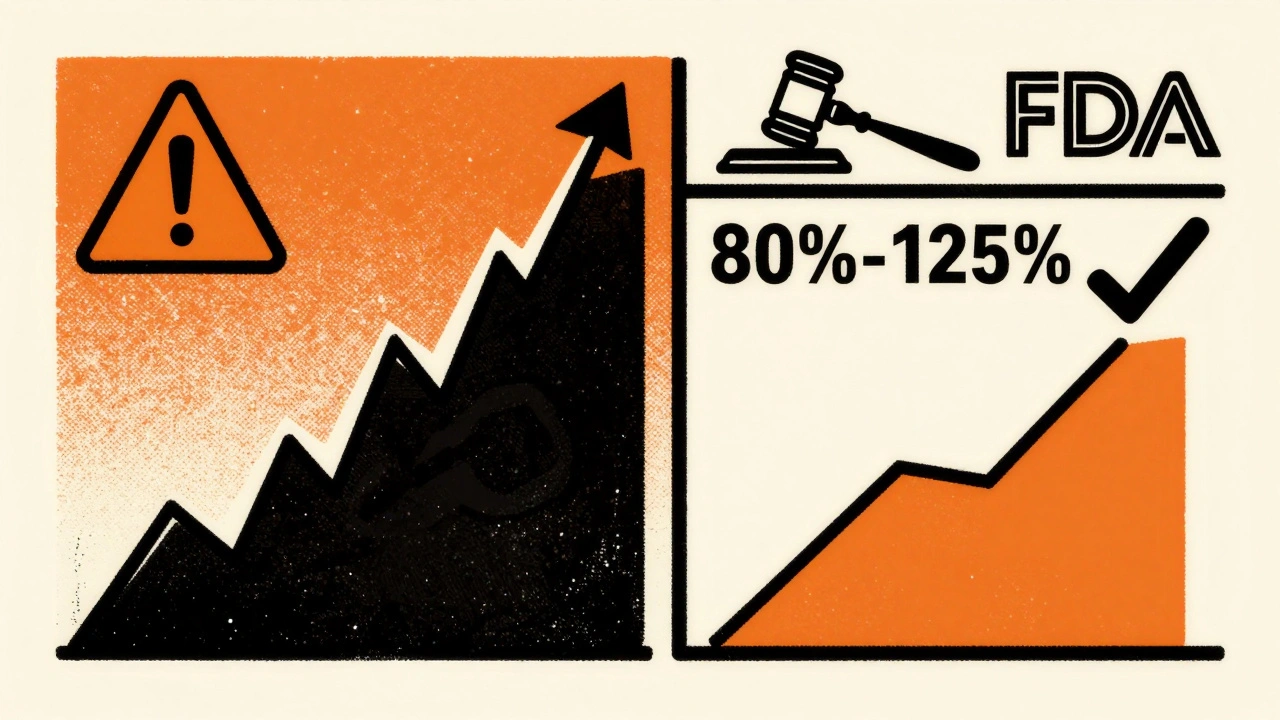

In bioequivalence studies, the generic version’s Cmax must be within 80% to 125% of the brand-name drug’s Cmax. That’s not arbitrary. It’s based on decades of data showing that differences beyond this range can lead to real-world effects. For example, a 2021 analysis of 500 bioequivalence studies found that 78% of generics had Cmax values within 90%-110% of the original. But even a 15% dip below the lower limit can mean slower pain relief-or worse, a seizure risk in epilepsy drugs.

What AUC Reveals About Total Exposure

If Cmax is the peak, AUC is the whole mountain range. AUC stands for area under the curve-a mathematical way of measuring how much drug your body is exposed to over time. It’s calculated by plotting blood concentration against time and measuring the space underneath that curve.

AUC tells you the total dose your body absorbs. For antibiotics like amoxicillin, it’s not enough to just hit a high peak-you need the drug to stay in your system long enough to kill bacteria. That’s where AUC comes in. A low AUC could mean the drug clears too fast, leading to treatment failure. A high AUC might mean buildup and toxicity.

Regulators require the generic’s AUC to also fall between 80% and 125% of the brand’s. This ensures the total drug exposure is nearly identical. In a real-world example from a 2007 study, a brand-name drug had an AUC of 124.9 mg·h/L, while its generic version measured 112.4 mg·h/L-a 90% ratio. That’s well within limits and confirmed as bioequivalent.

Why Both Metrics Are Non-Negotiable

You might think: if AUC covers total exposure, why do we even need Cmax? Because drugs don’t just behave like water filling a bucket. Some act fast and fade fast. Others creep in slowly and linger. Two drugs could have the same AUC but wildly different Cmax values-and that’s dangerous.

Imagine two painkillers with identical AUCs. One spikes to 10 mg/L in 1 hour (high Cmax, fast onset). The other climbs to only 6 mg/L but stays there for 8 hours (lower Cmax, slow release). The first gives quick relief but might cause nausea. The second avoids spikes but might not help acute pain. They’re not interchangeable. That’s why regulators insist on both.

The FDA and EMA both state clearly: both Cmax and AUC must pass the 80%-125% rule to declare bioequivalence. One failing means the whole study fails. No exceptions. This isn’t bureaucracy-it’s safety. In 2022, the FDA approved over 1,200 generic drugs. Every single one had to meet this dual standard.

How Bioequivalence Studies Work in Practice

These aren’t theoretical calculations. Real people take the drugs under strict conditions. Typically, 24 to 36 healthy volunteers participate in a crossover study: half take the brand first, then the generic after a washout period; the other half do the reverse. Blood is drawn 12 to 18 times over 3 to 5 half-lives of the drug-sometimes every 15 minutes in the first hour.

Why so many samples? Because missing the peak is the #1 reason studies fail. If you don’t sample frequently enough during the first 1-2 hours, you might miss Cmax entirely. Industry data shows this error causes about 15% of failed studies. Modern labs use LC-MS/MS machines that can detect drug levels as low as 0.1 ng/mL-enough to measure even tiny doses with precision.

The data then gets logged into software like Phoenix WinNonlin. Analysts transform the numbers using logarithms because drug concentrations follow a log-normal distribution-not a straight line. The ratios are calculated, confidence intervals are built, and the verdict comes down: pass or fail.

When the Rules Get Tighter

For most drugs, 80%-125% is fine. But for some, it’s not enough. Drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-like warfarin, lithium, or levothyroxine-have very little room for error. A 10% drop in AUC could mean a clot. A 10% rise could mean bleeding.

That’s why the EMA recommends tighter limits of 90%-111% for these drugs. The FDA allows it too, but only with extra proof. In 2022, the EMA published a reflection paper urging stricter standards for 15 key drugs. These aren’t theoretical-they’re life-or-death decisions.

And then there are highly variable drugs. Some people absorb them fast. Others absorb them slow. For these, the 80%-125% rule can unfairly block good generics. The EMA allows something called scaled average bioequivalence, which adjusts the limits based on how much the drug varies between people. The FDA has similar rules. But this is still debated. Some scientists worry it opens the door to weaker generics.

What’s Next for Bioequivalence?

Scientists are asking: Can we do better than just Cmax and AUC? For complex drugs-like extended-release pills that release in stages, or inhalers that deposit in the lungs-those two numbers might not tell the whole story.

The FDA’s 2023 draft guidance suggests looking at partial AUC for certain drugs. For example, if a drug releases in two waves, you might measure the first wave separately. This could help ensure the drug doesn’t spike too early or drop too soon.

There’s also talk of using computer models to predict bioequivalence without human trials. But experts agree: for now, nothing beats real blood samples. As Dr. Robert Lionberger of the FDA said in 2022: “AUC and Cmax will remain the primary endpoints for conventional drugs for the foreseeable future.”

Why? Because they’ve been tested for over 40 years. Because they’ve been used in thousands of studies. Because they’ve kept millions of patients safe.

Why This Matters to You

If you take a generic drug, you’re relying on Cmax and AUC. You don’t see them on the label. You don’t hear about them in ads. But they’re the invisible guarantee that your pill works just like the brand name.

That’s why regulators won’t cut corners. A drug that meets these standards has been proven to behave the same way in your body. It’s not guesswork. It’s science. And it’s why, according to a 2019 meta-analysis in JAMA Internal Medicine, there’s no meaningful difference in safety or effectiveness between generics and brand-name drugs that pass bioequivalence testing.

So next time you pick up a cheaper pill, remember: someone measured its peak. Someone calculated its exposure. And someone made sure it was safe for you.

What does Cmax mean in bioequivalence?

Cmax stands for maximum plasma concentration-the highest level a drug reaches in your bloodstream after taking it. In bioequivalence studies, it measures how quickly a generic drug is absorbed compared to the brand-name version. Regulators require the generic’s Cmax to be within 80%-125% of the original to ensure the drug works at the right speed.

What is AUC in bioequivalence testing?

AUC, or area under the curve, measures total drug exposure over time. It tells you how much of the drug your body absorbs from start to finish. For bioequivalence, the generic’s AUC must fall between 80% and 125% of the brand-name drug’s AUC. This ensures the overall amount of drug in your system is similar, which is critical for drugs that need sustained levels to work.

Why are both Cmax and AUC required for bioequivalence?

Because they measure different things. Cmax shows how fast the drug enters your system, which affects how quickly you feel its effects-or side effects. AUC shows how much total drug you’re exposed to, which affects how long it works. Two drugs can have the same AUC but very different Cmax values, meaning they behave differently in your body. Regulators require both to ensure safety and effectiveness.

What is the 80%-125% rule in bioequivalence?

The 80%-125% rule is the standard range regulators use to decide if a generic drug is bioequivalent to the brand-name version. It means the ratio of the generic’s Cmax or AUC to the brand’s must fall between 0.8 and 1.25. This range was chosen because differences outside it are likely to cause real clinical effects. It’s based on statistical analysis of decades of drug data and is used by the FDA, EMA, and over 120 countries.

Do all generic drugs need to meet Cmax and AUC standards?

Yes, for nearly all oral solid dosage forms like tablets and capsules. This is required by regulatory agencies worldwide to approve generic drugs under abbreviated pathways like the FDA’s ANDA. Some complex drugs-like injectables, inhalers, or extended-release formulations-may need additional testing, but Cmax and AUC remain the foundation for most generics.

Are there exceptions to the 80%-125% rule?

Yes, for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index (like warfarin or levothyroxine) or high variability. Regulators may tighten the range to 90%-111% to reduce risk. For highly variable drugs, some agencies allow scaled bioequivalence, where the acceptable range widens based on how much the drug varies between individuals. These exceptions are rare and require strong scientific justification.

13 Comments

Hamza LaassiliDecember 14, 2025 AT 05:04

Cmax?? AUC?? Who even cares as long as the pill works and costs less?? This is why america is broke-overanalyzing everything. Just let people take the cheap stuff!!!Webster BullDecember 14, 2025 AT 17:00

It's not overanalyzing. It's science. If you don't measure the peak and the total, you're gambling with lives.Yatendra SDecember 15, 2025 AT 21:02

I mean... 🤔 maybe we should just trust the chemists? 🧪💊sharon soilaDecember 16, 2025 AT 04:40

The science behind bioequivalence is one of the most important, yet least appreciated, public health safeguards we have. It ensures that millions of people can access life-saving medications without fear.Tyrone MarshallDecember 18, 2025 AT 02:02

I’ve seen patients panic when their generic switches. They think it’s not the same. But the data doesn’t lie. Cmax and AUC are the invisible hands keeping people alive. We owe it to them to keep these standards strict.kevin morangaDecember 18, 2025 AT 23:42

You know what’s wild? People will fight over a $5 difference on a prescription but won’t even think twice about how many blood draws, lab tests, and statistical models went into making sure that $5 pill won’t kill them. It’s like we’re allergic to gratitude for science.Emma SbargeDecember 20, 2025 AT 21:47

I work in a pharmacy. I’ve seen generics fail. Not because of the science-but because of bad manufacturing. That’s why we need these rules. Not because we’re paranoid. Because we’ve been burned before.Donna HammondDecember 22, 2025 AT 12:44

The 80%-125% range isn't arbitrary-it's based on decades of clinical outcomes. A 15% drop in Cmax for an epilepsy drug isn't just a number-it's a seizure waiting to happen. This isn't bureaucracy. It's prevention.Richard AyresDecember 23, 2025 AT 03:08

It's fascinating how something as abstract as an area under a curve can translate directly into someone’s ability to breathe, think, or survive. These metrics are poetry written in pharmacokinetics.Scott ButlerDecember 23, 2025 AT 22:13

If you're not from the U.S., you don't understand how hard we fight to keep generics safe. Other countries cut corners. We don't. This is American science at its best.Bruno JanssenDecember 25, 2025 AT 17:05

I wonder how many of these studies are rigged... I mean, who funds them? Big pharma? Or the generics? It's all smoke and mirrors, isn't it?Jennifer TaylorDecember 26, 2025 AT 03:13

I read somewhere that the FDA approved a generic that caused 3 deaths because the Cmax was just 2% off. They buried it. They always bury it. Why do you think the government won’t let you see the raw data?Tom ZerkoffDecember 27, 2025 AT 18:43

The fact that you can take a drug that was developed in the 1980s, replicate its pharmacokinetic profile with modern precision, and deliver it to a patient in rural Mississippi for a dollar-that’s one of the greatest achievements in modern medicine. Cmax and AUC aren’t just metrics. They’re justice.