When a pharmacist pulls a prescription off the system, they don’t just see "lisinopril." They see lisinopril 10 mg, NDC 00078-0123-01, TE code AB, from manufacturer A. Or they see "Zestril" 10 mg, NDC 00078-0124-01, TE code AB, from AstraZeneca. One is a generic. One is the brand. But to the patient, they’re the same pill. The system has to know the difference-not just for billing, but for safety, legality, and trust.

Why the distinction matters more than you think

Generic drugs aren’t cheaper because they’re weaker. They’re cheaper because they don’t need to repeat expensive clinical trials. The FDA requires them to have the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the brand. And they must be bioequivalent-meaning they deliver the same amount of drug into the bloodstream within the same time frame, with a 80-125% confidence interval. That’s not a guess. It’s science. But here’s the catch: not all generics are created equal in the eyes of the system. And not all systems handle them the same way. A pharmacy computer might show you 17 different versions of lisinopril. Only three of them are authorized generics-the exact same pill as the brand, just sold under a different label. The rest are independent generics. Some have different inactive ingredients. Some come from overseas manufacturers with different quality controls. The system needs to tell the difference.The backbone of identification: NDC and TE codes

Every drug in the U.S. has a National Drug Code (NDC). It’s a 10- or 11-digit number that breaks down into three parts: labeler code, product code, and package code. That’s how the system knows which company made it, what strength it is, and whether it’s a 30-tablet bottle or a 90-tablet bottle. But NDC alone isn’t enough. That’s where Therapeutic Equivalence (TE) codes come in. These two-letter codes, published in the FDA’s Orange Book, tell the system whether a generic can be swapped for the brand without risk. An "AB" code means it’s therapeutically equivalent. An "BX" means it’s not approved for substitution. An "A" followed by a letter (like AO or AN) means it’s a generic with special conditions. Pharmacy systems like Epic, Cerner, and Rx30 pull this data directly from the FDA’s Orange Book API, updated monthly. But here’s where things break: if the system isn’t syncing properly, a pharmacist might see a generic flagged as "not equivalent" when it actually is-or worse, the reverse. In 2021, the Institute for Safe Medication Practices reported 147 adverse events tied to incorrect substitution of warfarin, mostly because systems failed to block automatic swaps for this narrow therapeutic index drug.Authorized generics, branded generics, and the confusion they cause

Not all generics are straightforward. An authorized generic is made by the brand company itself and sold under a generic label. For example, the brand drug Prilosec (omeprazole) and its authorized generic are identical in every way-same factory, same pill, same packaging, just a different label. But pharmacy systems often don’t distinguish them from independent generics. A pharmacist might think they’re swapping to a cheaper version, when they’re actually swapping to the exact same product. Then there are branded generics. These are generics that have gone through the ANDA process but are marketed with catchy names like Errin, Jolivette, or Sprintec. They’re not the original brand, but they’re not called by their chemical name either. A patient might think they’re getting "the brand" because of the name. The system doesn’t always flag this. In a 2022 survey, 78% of pharmacists said they struggled to tell the difference between branded generics and true brands for birth control pills-especially when different chains use different names for the same product.How systems handle NTI drugs and safety alerts

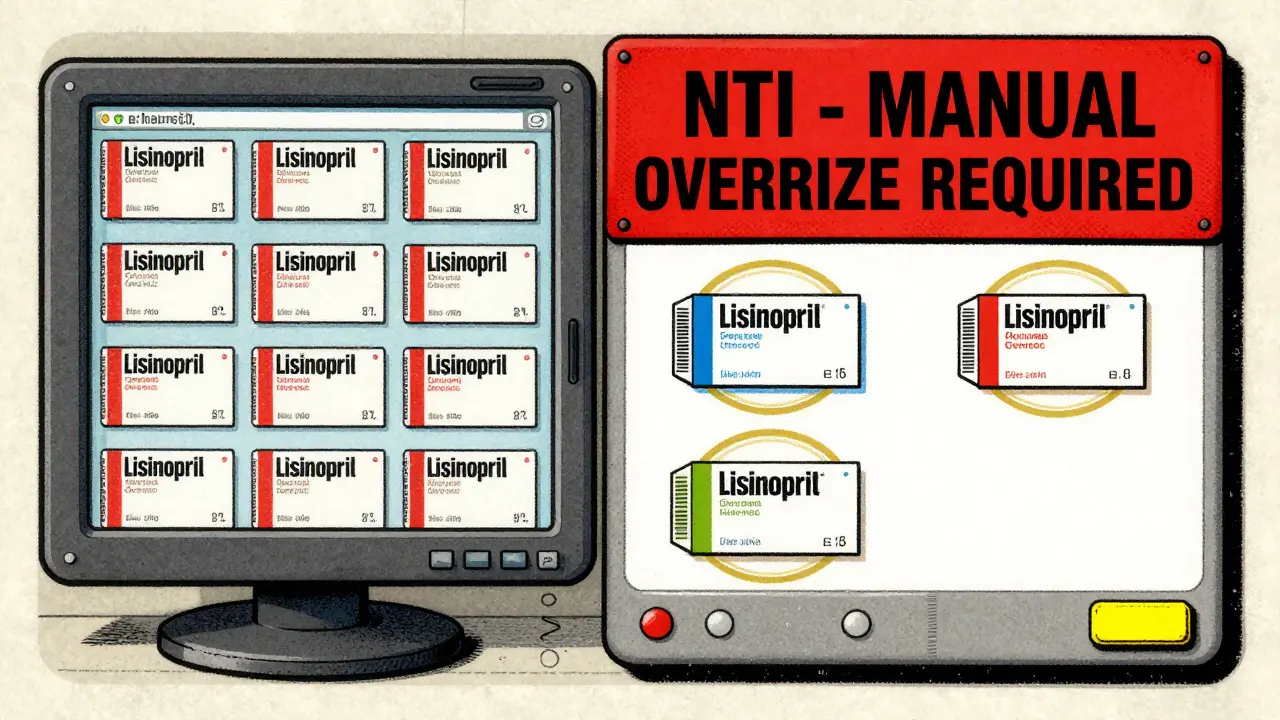

Some drugs can’t afford even tiny variations. These are called narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drugs. Warfarin, phenytoin, levothyroxine, cyclosporine, and lithium fall into this category. A 5% difference in blood levels can mean a stroke-or no effect at all. Smart pharmacy systems don’t allow automatic substitution for these. Epic’s Beacon Oncology module, for example, blocks generic swaps for warfarin unless a prescriber overrides it with a specific note. Kaiser Permanente’s system does the same. But many smaller pharmacies still use outdated systems that don’t have these safeguards. A 2023 study found that 31% of independent pharmacies still allow automatic substitution for NTI drugs because their software doesn’t flag them. The fix? Systems must integrate real-time FDA alerts for NTI drugs and require manual override for substitutions. But that requires configuration-and training. A 2022 ASHP report found that 62% of pharmacy staff had never received formal training on NTI drug substitution rules.

State laws and the patchwork of substitution rules

Federal law allows pharmacists to substitute generics unless the prescriber writes "dispense as written." But states have their own rules. California requires pharmacists to document why they didn’t substitute. Texas lets them substitute without telling anyone. New York requires a written note in the patient’s file. Florida mandates patient consent. Pharmacy systems must be configured to follow the state’s law automatically. But here’s the problem: NDC directories change 3,500 times a month. A new generic gets approved. An old one gets discontinued. A manufacturer changes its NDC. If the system isn’t updated daily, it’s giving outdated info. Only 89% of retail chains and 97% of hospital systems have automated updates. Independent pharmacies? Just 63%. Many still rely on manual lookups in the Orange Book-slow, error-prone, and outdated by the time they’re checked.What works: Kaiser Permanente’s model

Kaiser Permanente didn’t just upgrade software. They redesigned the workflow. Their system defaults to generics. But it doesn’t just swap blindly. It shows the patient and prescriber a side-by-side comparison: same active ingredient, same dose, same cost savings. It flags NTI drugs. It shows if a generic is authorized. It even links to educational videos. Result? In 2022, they dispensed generics 92.7% of the time. But more importantly, brand continuation requests dropped 37%. Why? Because patients understood the difference. They trusted the system. They weren’t surprised.What patients don’t know is hurting trust

A Consumer Reports survey in 2022 found that 68% of patients didn’t know generics have the same active ingredients as brands. When they got a different-looking pill, they assumed it was weaker. Or worse-fake. Pharmacists can’t fix that with a system update. They need to fix it with conversation. The best systems now include automated patient handouts or pop-up messages when a generic is dispensed: "This is the same medicine as [brand name], but less expensive. It works the same way." Reddit threads from pharmacists reveal how frustrating this gap is. One wrote: "I spent 15 minutes explaining to a patient why his new generic metoprolol wasn’t "cheap junk." He left angry. The system didn’t help me-it just showed me 17 options and told me to pick one."Best practices for pharmacy teams

1. Default to generics-but only if the system confirms therapeutic equivalence. Don’t assume. 2. Train staff on TE codes. Every technician and pharmacist should know what "AB," "BX," and "A" mean. Annual training isn’t optional-it’s a safety requirement. 3. Enable real-time FDA updates. Systems that don’t sync with the Orange Book API are ticking time bombs. 4. Block substitutions for NTI drugs unless overridden with documentation. No exceptions. 5. Use patient education tools. Don’t let patients walk out confused. Show them the science. Use visuals. Link to FDA videos. 6. Track authorized generics. If your system can’t tell you if a generic is made by the brand company, you’re missing a key layer of safety and cost control.The future: AI, interoperability, and precision

The FDA’s 2023 Orange Book modernization means real-time API updates are coming. No more 2-week delays. Systems will know the moment a new generic is approved. The 21st Century Cures Act now requires EHRs to include structured data fields that distinguish between reference drugs, authorized generics, and branded generics. That’s huge. It means your doctor’s system will know the difference before the prescription even reaches the pharmacy. And AI is stepping in. A 2023 study in JAMIA showed AI systems analyzing prescription patterns could predict substitution risks with 87.3% accuracy-especially for NTI drugs. Imagine a system that says: "This patient has been on brand levothyroxine for 8 years. Switching may trigger TSH fluctuations. Recommend holding unless prescriber approves." The next frontier? Pharmacogenomics. The FDA is exploring whether genetic markers could one day tell us which patients need the brand version of a drug-even if it’s bioequivalent. For now, that’s science fiction. But for some patients, it might become science fact.Bottom line: It’s not about brand vs generic. It’s about accurate identification.

The goal isn’t to push generics. It’s to make sure the right drug gets to the right patient at the right time. That means systems must be accurate, updated, and intelligent. It means staff must be trained. It means patients must be informed. The technology exists. The data is there. The regulations are clear. What’s missing is consistent implementation. And that’s where the real work begins.Are generic drugs really as effective as brand-name drugs?

Yes. The FDA requires generic drugs to have the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and bioequivalence as the brand-name version. This means they work the same way in the body. Studies show no meaningful difference in outcomes for most drugs. The only exceptions are narrow therapeutic index drugs like warfarin or levothyroxine, where small variations can matter-and even then, many patients do fine on generics with proper monitoring.

What’s the difference between an authorized generic and a regular generic?

An authorized generic is made by the same company that makes the brand-name drug, using the exact same formula and manufacturing process. It’s just sold under a generic label. A regular generic is made by a different company and must prove bioequivalence to the brand, but may have different inactive ingredients. Authorized generics are often identical to the brand in every way-down to the pill color and shape.

Why do some pharmacies charge more for generics?

Sometimes it’s because they’re dispensing a branded generic or an authorized generic, which may cost more than an independent generic. Other times, it’s due to pharmacy pricing policies or insurance formularies. A generic isn’t always the cheapest option-especially if the brand-name drug has a coupon or the insurance prefers a different generic version. Always check your receipt and ask your pharmacist if you’re unsure.

Can I ask my pharmacist to give me the brand instead of the generic?

Yes. You can ask for the brand-name drug, and your pharmacist can dispense it. But your insurance may charge you more, or you may have to pay the full price out-of-pocket. Some prescribers will write "dispense as written" on the prescription to prevent substitution. Always discuss cost and necessity with your pharmacist before deciding.

How do I know if my pharmacy system is up to date?

Ask your pharmacist if their system pulls data directly from the FDA’s Orange Book API and updates daily. If they say they manually check the Orange Book or haven’t updated their drug database in months, it’s outdated. Also, check if the system flags narrow therapeutic index drugs and shows TE codes. If it doesn’t, it’s not following current best practices.

Why do generic pills look different from the brand?

By law, generics can’t look exactly like the brand-name drug. This prevents confusion and trademark infringement. So they may be a different color, shape, or size. But the active ingredient and how it works in your body are the same. If you’re concerned, ask your pharmacist for the drug’s NDC code and look it up in the FDA’s database.

Do generics have the same side effects as brand-name drugs?

The active ingredient causes the same side effects. But sometimes, differences in inactive ingredients (like fillers or dyes) can cause minor reactions in sensitive patients-like stomach upset or rash. These are rare. If you notice new side effects after switching, tell your pharmacist or prescriber. It doesn’t mean the generic is weaker-it just means your body may react differently to the formulation.

Next steps: If you’re a pharmacist, audit your system’s TE code accuracy. If you’re a patient, ask your pharmacist to explain your medication label. If you’re a prescriber, use the "dispense as written" note only when clinically necessary-not because you’re unsure of generics. The system is only as good as the people using it-and the data feeding it.

11 Comments

kate jonesJanuary 31, 2026 AT 06:32

TE codes are the unsung heroes of pharmacy safety. AB doesn't just mean 'equivalent'-it means the FDA has validated bioequivalence across multiple batches, under varying pH and dissolution conditions. If your system isn't pulling from the Orange Book API daily, you're operating on folklore, not data. I've seen a BX-coded generic get auto-substituted because the system cached a 2021 version. Patient ended up with subtherapeutic INR. That’s not a glitch-that’s negligence.

And authorized generics? They’re the only generics that should ever be flagged as 'brand identical' in the UI. No ambiguity. No 'maybe.' If your EHR can't distinguish between an authorized generic and an independent one, it’s not just outdated-it’s dangerous.

Pharmacists aren’t just dispensers. We’re clinical gatekeepers. The system has to support that role-not undermine it.

Natasha PlebaniJanuary 31, 2026 AT 16:07

There’s a deeper philosophical tension here: identity versus equivalence. The pill is chemically identical, yes-but to the patient, the pill is its packaging, its color, its brand. The system treats drugs as data points. Humans treat them as symbols of trust.

When a patient sees a different-colored pill, they don’t think 'bioequivalence.' They think 'substitution.' And that’s not irrational-it’s psychological. The system’s failure isn’t technical; it’s phenomenological. We’ve optimized for efficiency, not meaning.

AI predicting substitution risk? Brilliant. But will it ever explain to Mrs. Henderson why her 80-year-old body reacts to the new filler in levothyroxine? No. That’s still a human job. And we’re abdicating it to code.

Maybe the real problem isn’t the NDC. It’s that we’ve forgotten that medicine isn’t just chemistry. It’s narrative.

owori patrickFebruary 2, 2026 AT 10:27

As a pharmacist in Nigeria, I see this differently. We don’t have FDA Orange Book. We don’t have NDC codes. We rely on WHO prequalification and local regulators who sometimes don’t update databases for months.

But here’s what works: we build trust with patients. We sit down. We show them the packaging. We say, 'This is the same medicine, just cheaper.' No jargon. No TE codes. Just honesty.

Our systems are outdated, yes. But our relationships? That’s our real safety net. Maybe the U.S. doesn’t need better software. Maybe it needs better conversations.

And if you’re a prescriber writing 'dispense as written' because you're afraid of generics? That’s not clinical judgment. That’s fear dressed up as caution.

April AllenFebruary 4, 2026 AT 06:18

NTI drugs are where the rubber meets the road. Warfarin isn’t just 'a drug.' It’s a tightrope. A 5% shift in bioavailability can kill. And yet, I’ve seen independent pharmacies still allow auto-substitution because 'it’s always worked before.'

It’s not about brand loyalty. It’s about pharmacokinetic precision. The FDA’s 80-125% range is a statistical band, not a guarantee for every individual.

My system blocks all substitutions for levothyroxine unless the prescriber adds 'substitution permitted' in the free text field. That’s not bureaucracy-it’s biochemistry.

And yes, we train every tech on TE codes. Twice a year. Because if you don’t know what 'AO' means, you shouldn’t be touching a prescription.

Kathleen RileyFebruary 6, 2026 AT 04:58

It is imperative to underscore, with the utmost gravity, that the contemporary pharmacy ecosystem is fundamentally compromised by the proliferation of nonstandardized, noninteroperable, and often antiquated technological infrastructures which fail to adhere to the rigorous, federally mandated benchmarks for therapeutic equivalence verification.

One cannot, in good conscience, permit the dispensation of pharmaceutical agents predicated upon data streams that are not dynamically synchronized with the authoritative repository of the FDA Orange Book, as such a practice constitutes a flagrant dereliction of professional duty and a violation of the Hippocratic Oath’s foundational tenet of nonmaleficence.

It is not merely a question of operational efficiency-it is a matter of moral accountability.

Beth CooperFebruary 8, 2026 AT 04:51

Let’s be real-this whole 'generic equals safe' thing is a corporate lie. The FDA doesn’t test every batch. Most generics are made in India or China. You think they’re using the same quality control as AstraZeneca? Please.

I switched to brand lisinopril after my rash came back. The generic had titanium dioxide. Brand didn’t. Coincidence? I don’t think so.

And don’t even get me started on 'authorized generics.' That’s just Big Pharma playing games-same pill, different label, same price. They’re laughing all the way to the bank.

My system? I manually override every single substitution. Because I’ve seen what happens when you trust the algorithm.

Donna FleetwoodFebruary 8, 2026 AT 08:27

Love this breakdown. Seriously. So many of us are just trying to do the right thing, but the system makes it feel like we’re playing whack-a-mole with pill colors and NDC codes.

But here’s the good news: when we take 30 seconds to explain to a patient why their new pill looks different-'It’s the same medicine, just cheaper, and here’s the FDA page that proves it'-they calm right down.

It’s not about the software. It’s about the moment you look someone in the eye and say, 'I’ve got you.'

Kaiser’s model? That’s the future. Not because it’s fancy tech. Because it’s human.

Melissa CogswellFebruary 8, 2026 AT 14:55

Just wanted to add: TE code training should be part of every new hire orientation. Not optional. Not ‘if you have time.’

I once had a tech substitute a BX-coded generic for metoprolol because she thought 'AB' and 'BX' were just version numbers. Patient’s HR spiked to 140.

We fixed the system. But we also made training mandatory. And now, every tech can tell you what 'A' means before their first shift.

It’s not glamorous. But it saves lives.

Shubham DixitFebruary 8, 2026 AT 15:19

Let me tell you something about American pharmacy systems-they’re overengineered and undertrained. In India, we have no NDC, no Orange Book, no AI. But we have something better: experience. We know our patients. We know their medicines. We know when something looks wrong.

You think your fancy Epic system is safer? I’ve seen a hospital in Mumbai with a handwritten logbook catch a dangerous substitution because the pharmacist remembered the patient’s last pill was white, not blue.

Technology is a tool, not a crutch. The real safety net isn’t the API-it’s the pharmacist who shows up, pays attention, and cares enough to ask, 'Wait, this doesn’t look right.'

Stop blaming the software. Start training your people. That’s where the real innovation is.

Blair KellyFebruary 10, 2026 AT 11:09

THIS IS A SCANDAL.

31% of independent pharmacies still allow NTI substitutions? That’s not negligence-that’s criminal. Someone’s going to die because a pharmacist didn’t know what 'AB' meant. And when that happens, the FDA will issue a press release. The hospital will issue an apology. And the system will get a $2 million upgrade.

But the patient? Dead.

And who pays? The family. The community. The moral fabric of healthcare.

It’s not a 'best practice.' It’s a底线. A line in the sand. And right now, we’re letting people step over it because it’s 'convenient.'

Fix the system. Or fix the people. But fix it. Now.

kate jonesFebruary 12, 2026 AT 04:29

Blair, you’re right. This isn’t about software-it’s about accountability. But let’s not pretend the answer is just 'train harder.'

The real fix is structural: mandate that every pharmacy system must have a real-time FDA feed, require TE code visibility on every screen, and make automatic NTI substitution a violation of state pharmacy board rules-with real penalties.

Training won’t save us if the system is designed to fail.

And if you think patients don’t notice when their pill changes color? They do. And they remember. That’s why Kaiser’s patient handouts work. They don’t just inform-they restore trust.

Systems that don’t do this aren’t outdated. They’re unethical.