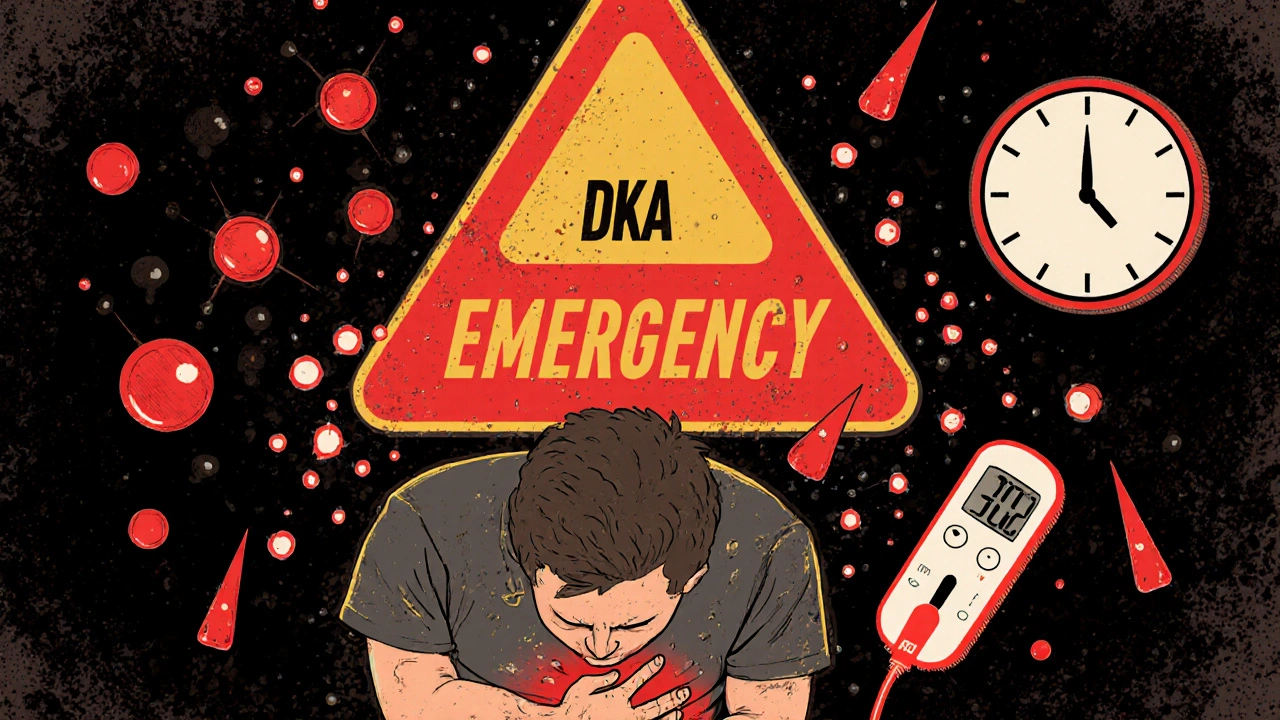

Diabetic ketoacidosis, or DKA, is not just a complication-it’s a medical emergency that can kill within hours if ignored. It doesn’t wait for a doctor’s appointment. It strikes suddenly, often in people who thought they were managing their diabetes fine. And too many people don’t recognize the signs until it’s too late. If you or someone you care about has type 1 diabetes-or even type 2 with little to no insulin production-you need to know what DKA looks like, how fast it moves, and what happens when you get to the hospital.

What DKA Actually Is

DKA happens when your body runs out of insulin. Without insulin, glucose can’t get into your cells for energy. So your body starts breaking down fat instead. That process produces ketones-acidic chemicals that build up in your blood. When ketones pile up, your blood turns acidic. That’s what makes DKA dangerous. Blood sugar is usually above 250 mg/dL, but not always. Some people develop euglycemic DKA, where blood sugar is normal or only slightly high, but ketones are still dangerously high. This is especially common in people taking SGLT2 inhibitors or during illness.

DKA mostly affects people with type 1 diabetes-about 80% of cases. But it can also happen in type 2 diabetes if insulin production drops sharply, like during severe infection, trauma, or if someone stops taking insulin because they can’t afford it. In kids, DKA is often the first sign that they have diabetes. About 30% of pediatric DKA cases are the first time the disease is ever diagnosed.

Early Warning Signs You Can’t Ignore

The first signs come on fast-usually within 4 to 12 hours. You might think it’s just the flu, a stomach bug, or dehydration. But these aren’t normal symptoms. They’re your body screaming for help.

- Extreme thirst-drinking 4 to 6 liters of water a day and still not satisfied.

- Frequent urination-going every hour, even at night. You might soak through sheets.

- Very dry mouth-so dry it hurts to swallow. This happens in nearly 9 out of 10 people with DKA.

- Blood sugar over 250 mg/dL-if you’re checking, this is your first red flag.

At this stage, you can still act. Check your ketones. If you have a blood ketone meter and it reads above 3 mmol/L, you need to go to the hospital-now. Don’t wait. Don’t call your doctor and wait for an appointment. Don’t try to "power through it."

When Symptoms Get Critical

If you don’t act in the next 12 to 24 hours, things spiral. The body’s acid levels rise. Your breathing changes. Your brain starts to fog.

- Nausea and vomiting-75% of people with DKA can’t keep anything down. Vomiting isn’t just uncomfortable-it’s a sign your body is shutting down.

- Abdominal pain-it can feel like appendicitis or food poisoning. That’s why 18% of adult DKA cases are misdiagnosed as gastroenteritis in emergency rooms.

- Extreme fatigue and weakness-you can’t stand up. You can’t walk to the bathroom. Your grip strength drops by 30-40%.

- Deep, rapid breathing-this is called Kussmaul respirations. It’s your body trying to blow off acid by breathing faster. It sounds like gasping. You might not even notice it’s happening until someone else points it out.

- Fruity-smelling breath-it smells like nail polish remover or overripe apples. That’s acetone, one of the ketones. Clinicians can smell it before they even test.

- Confusion or disorientation-if you’re having trouble thinking clearly, remembering names, or following simple instructions, you’re in danger.

- Loss of consciousness-this is a last resort. If someone passes out, call 999 immediately.

These aren’t "maybe" signs. They’re hard indicators that your blood is too acidic. If you have two or more of these symptoms and your blood sugar is over 250 mg/dL, go to the ER. No excuses.

What Happens in the Hospital

Once you’re admitted, the hospital team doesn’t waste time. They follow strict, evidence-based protocols to bring you back from the edge.

First: Fluids. You’re dehydrated-badly. The first hour is all about replacing lost fluid. You’ll get 15-20 mL per kilogram of body weight of saline solution-about 1 to 1.5 liters for most adults. This helps your kidneys flush out ketones and restores blood pressure.

Second: Insulin. You’ll get a small IV bolus of insulin, then a continuous drip. The goal isn’t to drop blood sugar fast-it’s to drop it steadily. Too fast, and you risk brain swelling, especially in children. The target is 50-75 mg/dL per hour. That’s slow enough to be safe, fast enough to save your life.

Third: Electrolytes. Your potassium is probably low-even if the blood test says it’s normal. Insulin pushes potassium into cells, and you’ve lost a lot through urine. You’ll get potassium IV, usually 20-30 mEq per hour, to keep your heart beating right. Sodium and chloride are also monitored closely.

Fourth: Monitoring. Blood sugar is checked every hour. Ketones are checked every 2-4 hours. Electrolytes every 2-6 hours. You’re not just getting treatment-you’re being watched like a hawk. The moment your blood pH climbs above 7.3 and ketones drop below 0.6 mmol/L, you’re on the road to recovery.

And here’s something you won’t hear often: you don’t need bicarbonate. Most hospitals still give it out of habit, but it’s not recommended unless your pH is below 6.9. That’s rare. And giving bicarbonate too early can make things worse.

How Long Do You Stay?

Most people stay 2.5 to 4 days. But your length of stay depends on how bad it was when you arrived. If your blood pH was 7.0 or lower, you’ll likely stay longer-around 3.8 days on average. If it was 7.1 or higher, you might be out in 2.1 days.

Discharge isn’t just about numbers. You need to be eating, drinking, and able to manage your insulin again. You’ll get a full education session before you leave. If you’re on an insulin pump, you’ll be told to switch to injections until you’re fully recovered. Infusion set failures cause 35% of pump-related DKA cases.

What Causes DKA? And Why It Keeps Happening

There are three big triggers:

- Infections-pneumonia, urinary tract infections, flu. They spike stress hormones, which block insulin.

- Missing insulin-whether it’s because you forgot, you ran out, or you couldn’t afford it. In the U.S., the average monthly insulin cost is $374. Some people ration. That’s how DKA starts.

- New-onset diabetes-especially in kids. Many are diagnosed in the ER because no one knew they had diabetes until they collapsed.

And here’s the ugly truth: DKA rates are rising in the U.S. by over 5% each year. Uninsured patients are 3.2 times more likely to get it. That’s not about medical failure-it’s about economic failure.

How to Prevent It

DKA isn’t inevitable. You can reduce your risk dramatically.

- Check ketones when blood sugar is over 240 mg/dL. Use a blood ketone meter if you can. Urine strips are outdated-they’re slow and inaccurate.

- Never skip insulin, even if you’re not eating. During illness, you need more insulin, not less.

- Use a CGM. People with continuous glucose monitors (like Dexcom G7) reduce DKA by 76%. High glucose and ketone alerts give you hours to act before you’re in crisis.

- Know your triggers. If you get sick, check ketones every 4 hours. Call your endocrinologist before you wait for an ER.

- Have a sick-day plan. Write it down. Include insulin dosing adjustments, when to call for help, and emergency contacts.

The FDA just approved the first DKA prediction algorithm-DiaMonTech’s DKA Risk Score. It uses CGM data to predict DKA 12 hours before it happens. It’s not everywhere yet, but it’s coming. That’s the future: prevention, not just treatment.

What Happens If You Wait Too Long

Every hour you delay fluids and insulin, your risk of death goes up by 15%. That’s not a guess. That’s from Dr. Irl Hirsch at the University of Washington, cited in Diabetes Care. And in children, cerebral edema-the brain swelling that comes from too-fast fluid correction-is the leading cause of death. It happens in 0.5-1% of cases, but 21-24% of those children die.

And if you’re misdiagnosed? That’s a nightmare. You’re sent home with anti-nausea meds. You keep vomiting. You get more dehydrated. You slip into a coma. By the time you’re back in the ER, you’re fighting for your life.

Can you have DKA with normal blood sugar?

Yes. This is called euglycemic DKA, and it accounts for about 10% of cases. It’s most common in people taking SGLT2 inhibitors (like dapagliflozin or empagliflozin) or during prolonged fasting, illness, or after bariatric surgery. Blood sugar might be under 250 mg/dL, even normal, but ketones are still dangerously high. If you’re on one of these medications and feel sick, check ketones-don’t wait for high blood sugar.

Can I treat DKA at home?

No. DKA requires hospital care. Even if you feel a little better after giving extra insulin or drinking water, you’re still at risk for dangerous complications like low potassium, brain swelling, or kidney failure. Home treatment doesn’t fix the acidosis or electrolyte imbalance. You need IV fluids, monitored insulin, and lab tests. Delaying hospital care increases your chance of death.

How do I know if my ketone level is dangerous?

On a blood ketone meter: under 0.6 mmol/L is normal. 0.6 to 1.5 mmol/L is mild and can be managed with extra insulin and fluids. 1.6 to 3.0 mmol/L is moderate-you should call your doctor immediately. Above 3.0 mmol/L is high and means you need emergency care. If you’re vomiting, confused, or having trouble breathing, go to the ER even if your ketones are below 3.0.

Why do I need to keep checking ketones after I feel better?

Because ketones can come back. Even if your blood sugar is normal and you’re not vomiting, your body might still be burning fat. Hospital discharge criteria require two consecutive readings showing ketones below 0.6 mmol/L, pH above 7.3, and bicarbonate above 18 mmol/L. Stopping too early leads to a 12% chance of DKA returning within 72 hours.

Should I stop my insulin pump if I’m sick?

Yes, switch to insulin injections during illness. About 35% of pump-related DKA cases happen because the infusion set got blocked, kinked, or dislodged-especially when you’re dehydrated or have an infection. Even if your pump looks fine, it might not be delivering insulin properly. Switching to shots ensures you’re getting the dose you need. Once you’re stable, you can go back to the pump.

Final Word: Don’t Wait for a Crisis

DKA doesn’t care if you’re busy, scared, broke, or tired. It doesn’t wait for insurance approval. It doesn’t care if you’ve been managing diabetes for years. One missed dose, one infection, one ignored symptom-and you’re in danger. The tools to prevent it exist: CGMs, ketone meters, sick-day plans, and education. Use them. Talk to your care team. Know your numbers. And if you see those signs-thirst, vomiting, fruity breath, confusion-don’t call your doctor. Go to the hospital. Your life depends on it.

10 Comments

Peter AultmanNovember 14, 2025 AT 01:23

Man, I never realized how fast DKA can hit. I’ve got a buddy with type 1 who checks his ketones every time his CGM spikes above 200. Said it saved his life last winter when he had the flu. No joke - he was fine until he started vomiting and thought it was just food poisoning. Thank god he had the meter.

Sean HwangNovember 14, 2025 AT 09:54

My cousin got diagnosed with type 1 in the ER after passing out. No one knew she had diabetes. She was 14. The docs said her ketones were over 5 and her pH was 7.0. They kept her for 4 days. Now she’s got a CGM and a sick day plan. Everyone needs to know this stuff.

kshitij pandeyNovember 14, 2025 AT 18:27

This is the kind of info every family should have printed and taped to the fridge. In India, so many kids get diagnosed late because parents think diabetes is just about sugar. This post could save lives if shared in local groups. Thank you for writing it clearly.

Dilip PatelNovember 15, 2025 AT 19:34

People in the US act like DKA is some rare thing but in developing countries its a death sentence because insulin costs more than a month’s rent. You talk about SGLT2 inhibitors like they’re magic but most of us cant even afford regular insulin. This post is full of privilege and zero solutions.

Jane JohnsonNovember 16, 2025 AT 17:25

While the clinical information presented is undeniably accurate, one cannot overlook the systemic failures that render preventive measures inaccessible to vast segments of the population. The emphasis on personal responsibility, while well-intentioned, ignores the structural barriers to healthcare equity.

Sean EvansNovember 16, 2025 AT 19:33

Wow. So you’re telling me people die because they can’t afford insulin? 😭 That’s not a medical problem - that’s a moral failure. I’m crying right now. Why is this still happening in 2025? 🤬 Someone needs to burn down the pharmaceutical CEOs’ houses. I’m not even joking.

Barry SandersNovember 18, 2025 AT 09:05

Typical. Another post full of fearmongering. You say go to the ER if ketones are above 3 - but what if you’re in rural Alaska with no hospital for 200 miles? Or if you’re undocumented? Your advice is useless to 40% of people who need it.

Chris AshleyNovember 19, 2025 AT 13:51

My pump got clogged once during a hike and I didn’t realize until I started feeling weird. I threw up for 6 hours. Ended up in the ER. Now I carry spare pens and a backup kit everywhere. Don’t be like me. Be prepared.

Peter AultmanNovember 20, 2025 AT 17:55

Chris Ashley nailed it. I had the same thing happen last summer. Thought my pump was fine. Turned out the tubing had a tiny kink. Took me 12 hours to realize I was going into DKA. If I hadn’t had a ketone meter, I’d be dead. Seriously - check your gear. Always.

Brittany CNovember 22, 2025 AT 05:11

It’s worth noting that the ADA guidelines now explicitly recommend against bicarbonate administration in DKA unless pH < 6.9, as per the 2023 Standards of Care. The evidence for harm from alkalinization is robust, yet many EDs still default to it out of habit. This is a critical update for clinicians.