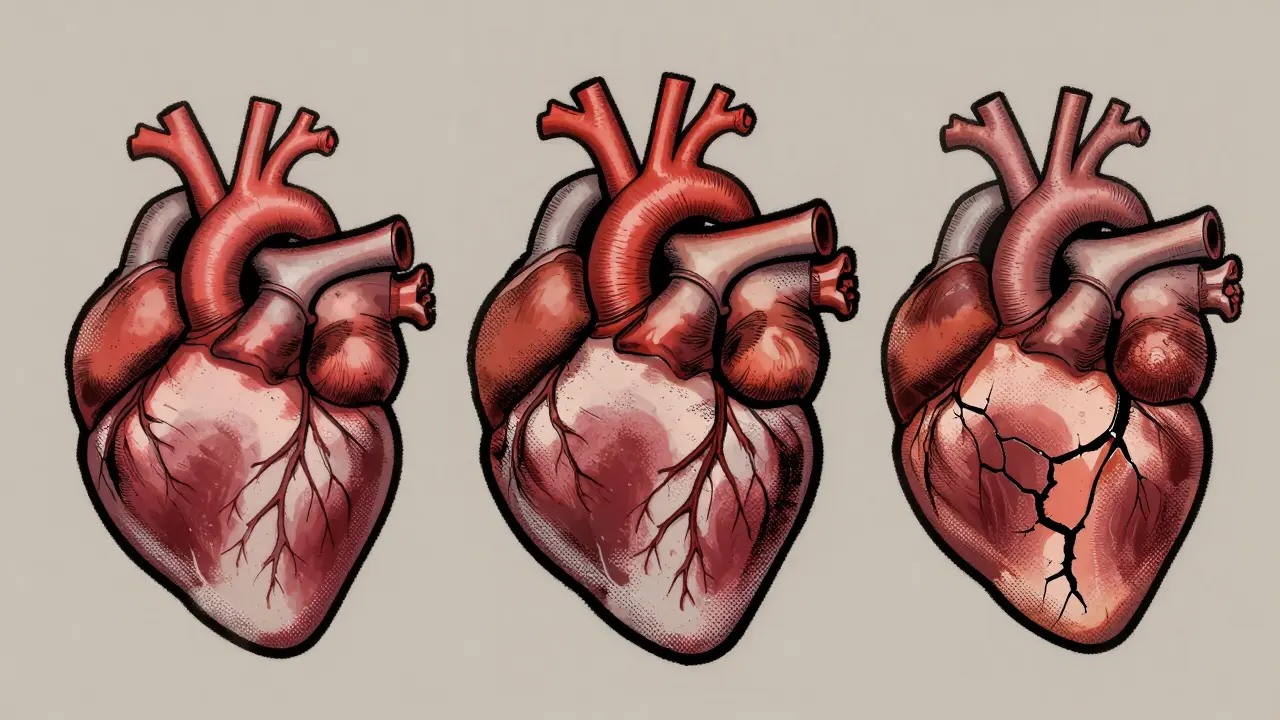

When your heart muscle doesn’t work right, it doesn’t just feel like fatigue-it can be life-threatening. Cardiomyopathy isn’t one disease. It’s a group of conditions where the heart muscle changes shape, thickens, or stiffens, making it harder to pump blood. About 1 in 250 adults has some form of it. And while many people think of heart attacks or clogged arteries when they think of heart problems, cardiomyopathy is different. It’s a disease of the muscle itself, not the pipes. The three main types-dilated, hypertrophic, and restrictive-make up 90% of all cases. Each one behaves differently, needs different tests, and demands its own treatment plan.

Dilated Cardiomyopathy: The Heart That Stretches Too Far

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is the most common type. Think of it like a balloon that’s been overinflated. The left ventricle-the heart’s main pumping chamber-gets stretched out, thin, and weak. Its walls, which should be strong and thick, drop below 10 millimeters. The chamber size balloons past 55 mm in men or 50 mm in women. The result? The heart can’t squeeze hard enough. Ejection fraction, the measure of how much blood it pushes out with each beat, falls below 40%. Normal is 55-70%.

Why does this happen? Sometimes, it’s genetic. About 30% of cases run in families, often linked to mutations in genes like TTN or LMNA. Other times, it’s caused by damage. Heavy drinking-more than 80 grams of alcohol a day for five years-can poison the heart muscle. Chemotherapy drugs like doxorubicin, especially after a cumulative dose over 450 mg/m², can trigger it. Viral infections, like coxsackievirus, can inflame the heart and leave it scarred and weak. Autoimmune diseases like sarcoidosis can also attack the muscle.

People with DCM often feel winded climbing stairs, swell in their legs, or wake up gasping at night. Diagnosis starts with an echocardiogram, which shows the enlarged chamber and weak squeeze. A cardiac MRI confirms if there’s scarring or fibrosis-key clues for prognosis. Genetic testing is recommended if there’s a family history. Treatment follows a four-pillar approach: ARNI drugs like sacubitril/valsartan (which reduce hospitalizations by 20% compared to older meds), beta-blockers to slow the heart, SGLT2 inhibitors (originally diabetes drugs that now protect the heart), and sometimes an implantable defibrillator if the risk of sudden death is high. With treatment, 70-80% of patients survive five years. Without it? The numbers drop fast.

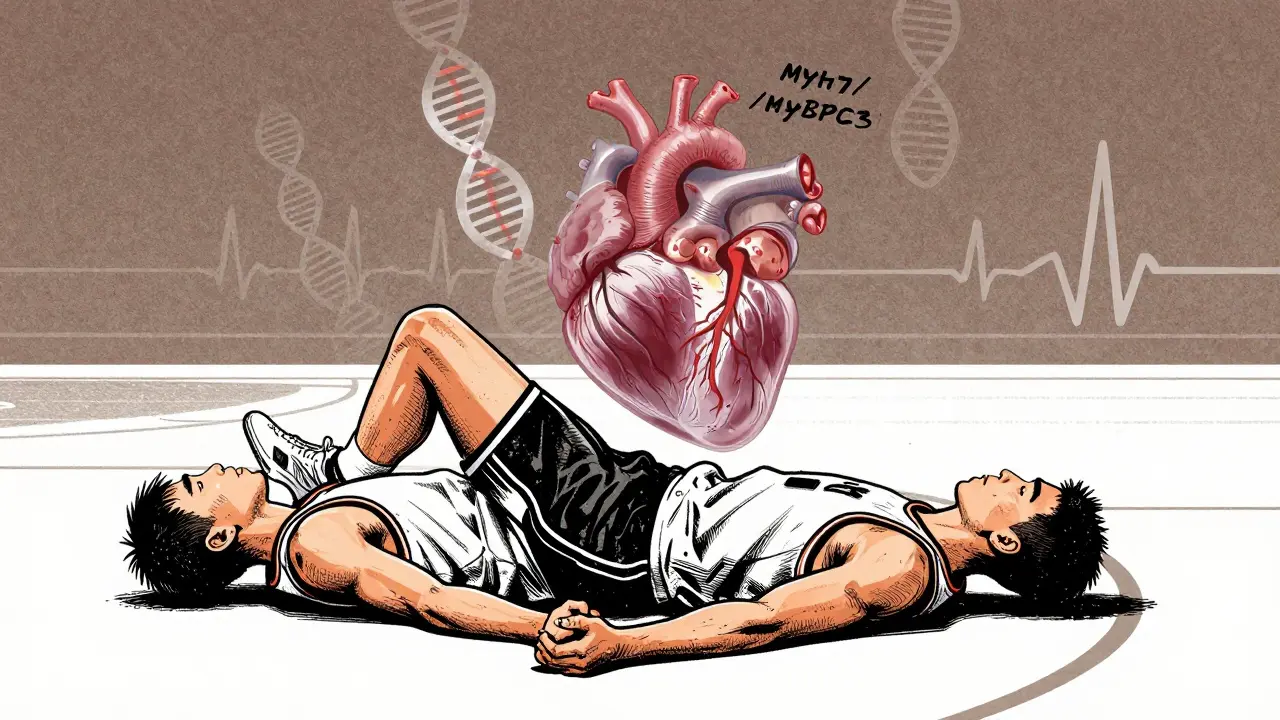

Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: The Heart That Thickens Without Reason

If DCM is the stretched heart, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is the packed one. The muscle thickens-sometimes dramatically-without any obvious cause like high blood pressure or valve disease. Walls hit 15 mm or more. In some cases, the thickening is uneven, with the wall between the chambers (the septum) bulging more than the rest. That’s called asymmetric septal hypertrophy. The heart becomes stiff, not weak. It struggles to relax and fill with blood between beats. That’s diastolic dysfunction.

HCM is genetic in 60% of cases. Mutations in MYH7 or MYBPC3 genes mess up the heart’s contractile machinery. It’s passed down in an autosomal dominant pattern-just one copy of the faulty gene can cause it. That’s why family screening is critical. One in 500 people in the U.S. has HCM, but only 10% know it. Athletes are especially at risk. HCM is the leading cause of sudden cardiac death in young athletes under 35, accounting for 36% of those tragedies.

Some people with HCM have no symptoms. Others get chest pain, dizziness, or fainting during exercise. The biggest danger? Obstruction. In 70% of cases, the thickened septum blocks blood flow out of the heart. This creates a pressure gradient of 30 mmHg or more. That’s when symptoms spike. Diagnosis relies on echocardiography and cardiac MRI. Genetic testing (a 17-gene panel) confirms the cause in 60% of cases. Treatment isn’t one-size-fits-all. Beta-blockers help 70% of patients by slowing the heart and improving filling. For those with obstruction, drugs like disopyramide or surgical options like septal myectomy or alcohol ablation can reduce the blockage. In 2022, the FDA approved mavacamten (Camzyos), a first-of-its-kind drug that directly targets the overactive heart muscle. It cuts the outflow gradient by 80% in most patients. But it’s expensive-$145,000 a year. Still, for many, it’s life-changing.

Restrictive Cardiomyopathy: The Heart That Won’t Fill

Restrictive cardiomyopathy (RCM) is the rarest-only 5% of cases-but often the most deadly. The heart muscle doesn’t stretch or thicken. It just gets stiff. Like a rubber band that’s lost its elasticity. The chambers stay small, the walls stay thin (under 12 mm), and the heart can’t relax enough to fill with blood. The pumping function looks normal-ejection fraction stays above 50%. But without enough blood inside, the heart can’t push enough out. That’s why symptoms look like heart failure: swelling, fatigue, shortness of breath-even though the squeeze is strong.

RCM isn’t usually inherited. It’s caused by other diseases that invade the heart. Amyloidosis is the biggest culprit-60% of cases. Tiny protein fibers build up in the muscle, like concrete in a sponge. Sarcoidosis, hemochromatosis (too much iron), and Fabry disease (a rare genetic storage disorder) can also do it. The heart doesn’t just get stiff-it gets infiltrated. That’s why cardiac MRI is so important. It shows late gadolinium enhancement in a patchy, non-coronary pattern, and extracellular volume above 35% confirms fibrosis or infiltration.

Diagnosing RCM is tricky. It looks a lot like constrictive pericarditis-a disease of the sac around the heart. But the treatments are completely different. One needs surgery to remove the sac. The other needs to treat the underlying disease. That’s why endomyocardial biopsy (taking a tiny heart tissue sample) is often needed. For amyloidosis, drugs like tafamidis can slow progression and improve walking distance by 25 meters. But it costs $225,000 a year. For hemochromatosis, regular blood removal (phlebotomy) can help. For sarcoidosis, steroids or immunosuppressants are used. Prognosis is grim without treatment. Survival drops to 30-50% at five years. Even with treatment, outcomes lag behind DCM and HCM.

How They Compare: Side by Side

| Feature | Dilated (DCM) | Hypertrophic (HCM) | Restrictive (RCM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heart Chamber Size | Enlarged | Normal or small | Normal or small |

| Wall Thickness | Thin (<10 mm) | Thick (>15 mm) | Normal (<12 mm) |

| Main Problem | Poor squeezing (systolic failure) | Poor relaxing (diastolic failure) | Poor relaxing (diastolic failure) |

| Ejection Fraction | <40% | >50% | >50% |

| Common Causes | Genetics, alcohol, chemo, viruses | Genetics (sarcomere mutations) | Amyloidosis, sarcoidosis, hemochromatosis |

| Diagnostic Tool | Echocardiogram + MRI | Echocardiogram + MRI + genetic test | Echocardiogram + MRI + biopsy |

| 5-Year Survival (with treatment) | 70-80% | 70-95% | 30-50% |

What’s New in Treatment and Research

Cardiomyopathy care is changing fast. In 2024, gene therapy trials are starting. The VERVE-201 trial is using CRISPR to edit the MYBPC3 gene in HCM patients-a one-time fix that could prevent the disease from being passed on. For DCM, AAV1/SERCA2a gene therapy is being tested to boost calcium handling in heart cells. These aren’t cures yet, but they’re promising.

Drugs are also getting smarter. SGLT2 inhibitors, once used only for diabetes, now reduce heart failure hospitalizations across all types. ARNI drugs like sacubitril/valsartan have replaced older ACE inhibitors as the gold standard for DCM. And for amyloidosis, new monoclonal antibodies like daratumumab are showing real survival benefits.

But access is still unequal. Only 35% of community hospitals correctly classify cardiomyopathy types. Rural areas lack specialists. Genetic testing costs $1,200-$2,500. Life-saving drugs like tafamidis and mavacamten cost over $100,000 a year. Insurance coverage varies wildly. That’s why early diagnosis matters more than ever.

What You Should Know If You’re Diagnosed

If you or someone you love has been diagnosed with one of these types, here’s what to do:

- Get a cardiac MRI. It shows scarring, infiltration, and fibrosis better than any other test.

- Ask about genetic testing. Especially if there’s family history. It changes screening for relatives.

- Know your ejection fraction and wall thickness. These numbers guide treatment.

- Don’t ignore symptoms. Fatigue, swelling, or fainting aren’t normal aging.

- Ask about clinical trials. New drugs and gene therapies are opening up options.

Cardiomyopathy isn’t a death sentence anymore. With the right diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring, many people live full lives. But it takes knowing which type you have-and why it matters.

Can you have more than one type of cardiomyopathy at the same time?

No, you don’t typically have two types simultaneously. But one type can evolve into another over time. For example, long-standing DCM can lead to secondary thickening that mimics HCM. Or, in advanced RCM, the heart may eventually dilate due to chronic pressure overload. The classification is based on the dominant pattern at diagnosis. If the pattern changes, doctors reclassify it.

Is cardiomyopathy hereditary?

Yes, especially HCM and DCM. About 30-40% of DCM cases and 60% of HCM cases have a genetic cause. If you have one of these types, your first-degree relatives (parents, siblings, children) should be screened with an echocardiogram and possibly genetic testing. Even if they have no symptoms, early detection can prevent sudden death.

Can exercise worsen cardiomyopathy?

It depends. With DCM, moderate aerobic exercise is encouraged-it improves heart efficiency. With HCM, intense competitive sports are dangerous and often banned due to sudden death risk. Low-intensity activities like walking or cycling are usually safe. With RCM, exercise tolerance is limited by stiffness, so activity should be guided by symptoms. Always get clearance from a cardiologist before starting or changing an exercise routine.

How do you know if it’s cardiomyopathy and not just heart failure?

All cardiomyopathies cause heart failure, but not all heart failure comes from cardiomyopathy. Heart failure can also be caused by high blood pressure, valve leaks, or coronary artery disease. Cardiomyopathy means the heart muscle itself is diseased, without those other causes. Doctors rule out those conditions first. If the heart muscle is abnormal and no other cause fits, it’s cardiomyopathy.

Can you live a normal life with restrictive cardiomyopathy?

It’s harder than with other types. RCM has the poorest survival rate. But some people do live for years with careful management. Treating the root cause-like amyloidosis with tafamidis or hemochromatosis with phlebotomy-can slow progression. Many need diuretics to control fluid, and some require heart transplants. Quality of life is often reduced due to fatigue and activity limits, but with expert care, many maintain meaningful daily routines.

Next Steps If You Suspect Cardiomyopathy

If you’re experiencing unexplained shortness of breath, fatigue, swelling, or fainting, don’t wait. See a cardiologist. Start with an echocardiogram-it’s non-invasive, quick, and the first step for all three types. If results are unclear, ask about cardiac MRI. If there’s a family history of sudden death or heart disease before age 50, push for genetic counseling. Early detection saves lives. And with new treatments on the horizon, knowing your type isn’t just about diagnosis-it’s about access to better care.

10 Comments

Juan ReibeloJanuary 24, 2026 AT 02:09

Wow, this is one of the clearest breakdowns of cardiomyopathy I’ve ever read. Seriously, someone should turn this into a pamphlet for GPs. I had no idea DCM could come from chemo-I’m a cancer survivor, and my cardiologist never mentioned it. Now I’m asking for an echo next visit. Thanks for laying it out like this.

Dolores RiderJanuary 25, 2026 AT 11:54

They’re hiding the truth about these drugs… I read on a forum that the FDA approves them just to keep Big Pharma rich. Tafamidis costs $225K? That’s not medicine-that’s a ransom note. And don’t get me started on gene therapy… they’re already testing CRISPR on humans? Who’s signing the consent forms? 😡

John McGuirkJanuary 26, 2026 AT 11:07

Yeah right. 1 in 250 adults has it? More like 1 in 25 if you count the ones who don’t get tested. My uncle died at 47 from ‘sudden heart failure’-no diagnosis, no MRI, just a death certificate that said ‘natural causes.’ They don’t want you to know how many people they miss. And don’t even get me started on how they ignore RCM because it’s ‘rare.’

Michael CamilleriJanuary 26, 2026 AT 13:36

People think medicine is about saving lives but it’s really about control. You get diagnosed with HCM and suddenly you’re not allowed to run, lift, laugh too hard. They give you beta-blockers to numb you so you don’t question why your body betrayed you. The real cure isn’t in a pill-it’s in waking up and rejecting the system that turned your heart into a liability

Darren LinksJanuary 27, 2026 AT 09:38

So we’re spending six figures on drugs for rich people while veterans can’t get heart meds at the VA? That’s the American dream right there. If you’re poor and have RCM, you’re just supposed to die quietly. I’m not mad, I’m just disappointed. This isn’t healthcare-it’s a luxury subscription.

Kevin WatersJanuary 29, 2026 AT 03:11

This is such a helpful guide. I work in a rural clinic and we rarely see cardiologists. I’m printing this out for our nurses and sharing it with patients who come in with unexplained fatigue. The table comparing the three types? Gold. And the note about cardiac MRI being critical-that’s something we can push for even if insurance is slow. Thank you for making this so actionable.

Sawyer VitelaJanuary 30, 2026 AT 00:28

DCM: thin walls. HCM: thick walls. RCM: stiff walls. Done. You’re welcome.

Tiffany WagnerJanuary 31, 2026 AT 02:17

I had HCM and didn’t know it until I passed out at yoga. My doctor said ‘it’s probably nothing’… turns out my septum was 22mm. I’m alive because I pushed for a second opinion. Don’t let anyone brush off your symptoms. You know your body best.

Chloe HadlandJanuary 31, 2026 AT 06:04

Thank you for writing this. I’ve been scared to ask my dad about his heart-he’s 68 and has had fatigue for years. Now I know what questions to ask. I’m getting him an echo next week. I’m so glad there’s hope, even with RCM.

Amelia WilliamsFebruary 1, 2026 AT 20:56

Gene therapy sounds like sci-fi but it’s real? I’m crying. My cousin has TTN mutation and is 12. If this works, she could grow up without a heart transplant. I’m sharing this with every family group chat. We need to fund this research. Not just for us-for everyone.