When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you might wonder: is this really the same as the brand-name drug you’ve been taking? The answer isn’t just "yes"-it’s backed by a strict, science-based system called bioequivalence. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) doesn’t just approve generic drugs because they look alike or cost less. They require proof that the generic works the same way in your body as the original. This isn’t guesswork. It’s a detailed, regulated process that ensures safety and effectiveness.

What Bioequivalence Really Means

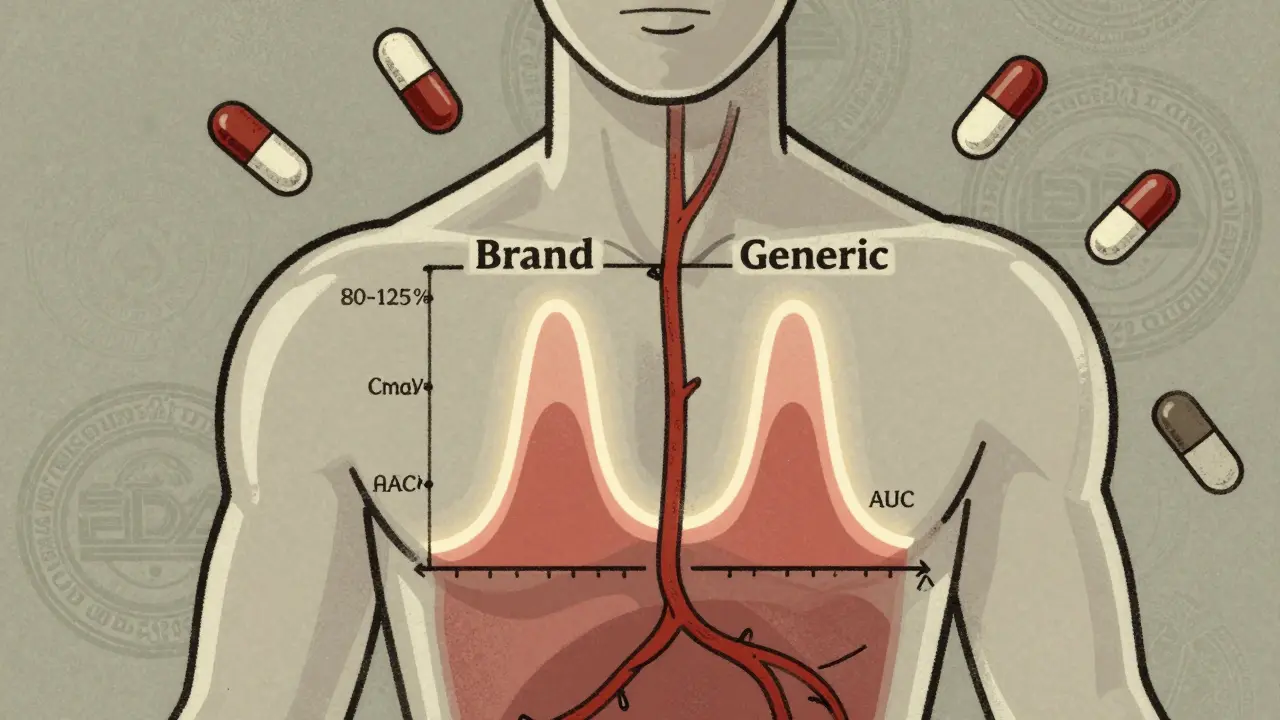

Bioequivalence isn’t about matching ingredients by weight. It’s about matching how your body handles the drug. The FDA defines it as "the absence of a significant difference in the rate and extent to which the active ingredient becomes available at the site of drug action." In plain terms: if you take a generic version of a drug, your body should absorb it at nearly the same speed and in nearly the same amount as the brand-name version.

This matters because how fast and how much of a drug enters your bloodstream determines whether it works properly. Too little, and it won’t help. Too much, and it could cause side effects. For most drugs, the difference between effective and dangerous is small. That’s why the FDA doesn’t rely on patient trials for generics. Instead, they use pharmacokinetic studies-tests that measure what happens to the drug inside the body after it’s taken.

How the FDA Tests for Bioequivalence

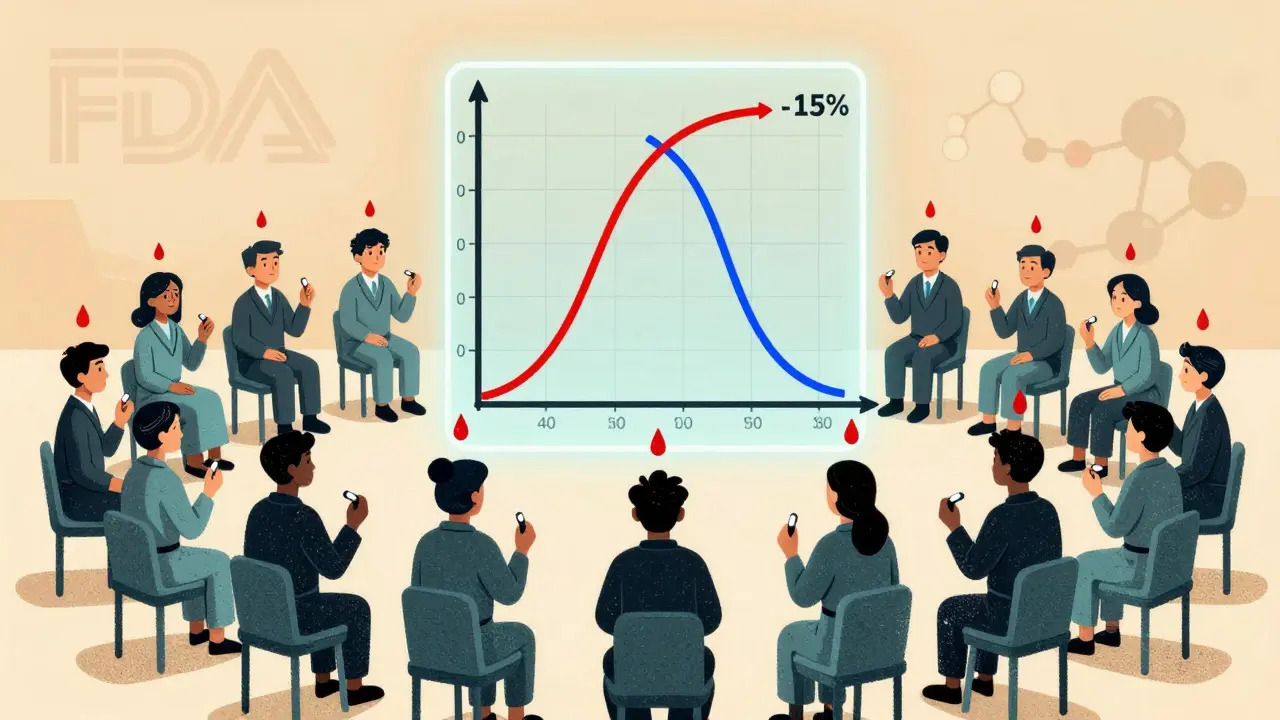

To prove bioequivalence, manufacturers run controlled studies with 24 to 36 healthy volunteers. These are crossover trials, meaning each person takes both the brand-name drug and the generic, at different times, under the same conditions. Blood samples are taken over hours to track how the drug moves through the body.

Two key numbers are measured:

- Cmax: The highest concentration of the drug in the blood after dosing. This tells you how fast the drug is absorbed.

- AUC: The total amount of drug absorbed over time. This tells you how much of the drug your body actually gets.

The FDA requires that the ratio of the generic’s Cmax and AUC to the brand-name drug’s values must fall between 80% and 125%. But here’s what most people don’t understand: this isn’t a range for the active ingredient’s amount in the pill. It’s a range for how your body responds to it.

For example, if the brand-name drug gives an AUC of 100 units, the generic must show an AUC between 80 and 125 units. But it’s not enough for the average to be within that range. The 90% confidence interval-a statistical range that shows how consistent the results are-must also fit entirely inside 80-125%. If the average is 110%, but the confidence interval stretches from 95% to 130%, the study fails. Why? Because there’s a chance the drug could be too strong in some people.

This system ensures that even with normal variations in how people absorb drugs, the generic will still be safe and effective for nearly everyone.

Common Misconceptions About Generic Drugs

One of the biggest myths is that generics can contain anywhere from 80% to 125% of the active ingredient. That’s wrong. The active ingredient in a generic must be identical in amount to the brand-name drug. The 80-125% range applies only to how your body processes it-not how much is in the tablet.

Another myth is that generics are "weaker" or "less pure." In reality, the FDA requires generics to meet the same purity, strength, and quality standards as brand-name drugs. The difference isn’t in the medicine-it’s in the packaging, the color, the shape, and the price.

Even some healthcare providers get confused. A 2015 study in PubMed showed that many doctors mistakenly believed generics could legally contain 80-125% of the active ingredient. That misunderstanding can lead to unnecessary hesitation when prescribing generics. The science doesn’t support it. The FDA’s standards are designed to eliminate clinical risk.

Pharmaceutical Equivalence vs. Bioequivalence

Before a generic can be approved, it must first meet two criteria:

- Pharmaceutical equivalence: Same active ingredient, same strength, same dosage form (tablet, capsule, etc.), same route of administration (oral, injection, etc.), and same labeling.

- Bioequivalence: Same performance in the body, as proven by pharmacokinetic studies.

One without the other isn’t enough. A pill could have the exact same ingredients but dissolve too slowly in your stomach, meaning it won’t be absorbed properly. That’s why both steps are required. The FDA’s product-specific guidances-over 2,000 as of 2023-tell manufacturers exactly how to test each drug. Some drugs need in vivo testing (in people). Others, like topical creams or inhalers, might rely on in vitro testing (lab-based) if absorption isn’t systemic.

Why This System Works

The bioequivalence framework was created by the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984. Before that, generic manufacturers had to repeat all the expensive clinical trials done by the brand-name company. That made generics too costly to produce. Hatch-Waxman changed that. It allowed generics to rely on the original safety data, as long as they proved bioequivalence.

This move saved the U.S. healthcare system an estimated $1.7 trillion between 2010 and 2019. Today, 90% of prescriptions filled are for generics-but they make up only about 20% of total drug spending. The system works because it’s based on real data, not assumptions.

The FDA’s Office of Generic Drugs reviews about 1,000 Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDAs) each year. Bioequivalence studies are the most common reason for rejection. Issues like inconsistent dissolution rates, poor formulation, or manufacturing flaws can cause a study to fail. Manufacturers often go back, tweak the formula, and resubmit.

What About Drugs With Narrow Therapeutic Index?

Some drugs are so sensitive that even tiny changes in blood levels can cause harm. Think of blood thinners like warfarin, anti-seizure drugs like phenytoin, or thyroid medications like levothyroxine. For these, the FDA still uses the 80-125% rule-but they monitor them more closely.

Studies have shown that generics for these drugs perform just as well as brand-name versions when bioequivalence is properly demonstrated. The FDA doesn’t tighten the range because the standard has proven safe across decades of use. But they do require more data and post-market monitoring for these products.

Transparency and the Future of Generic Approval

In 2021, the FDA changed its rules to require manufacturers to submit all bioequivalence studies they’ve done-not just the successful ones. This means if a company ran five studies and only one passed, they still have to report the other four. This reduces bias and gives regulators a clearer picture of how the drug behaves.

The FDA is also exploring new methods to reduce the need for human studies. For some complex drugs-like inhalers, patches, or injectables-modeling and simulation tools are being tested. These computer-based models predict how a drug will behave in the body based on physical and chemical properties. If proven reliable, they could replace some clinical trials in the future.

Industry analysts expect a 20% annual growth in approvals for complex generics through 2025. As technology improves, the system will become even more efficient-without sacrificing safety.

What This Means for You

If you’re prescribed a generic drug, you can trust it. The FDA’s bioequivalence standards aren’t a shortcut-they’re a rigorous, science-backed guarantee. The same active ingredient. The same dosage. The same effectiveness. And a fraction of the cost.

There’s no need to pay more for a brand name unless your doctor specifically recommends it. For over 90% of prescriptions, the generic is not just cheaper-it’s just as good.

Do generic drugs contain the same active ingredient as brand-name drugs?

Yes. Generic drugs must contain the same active ingredient, in the same strength and dosage form, as the brand-name version. The FDA requires exact matching of the active component. Differences in inactive ingredients (like fillers or dyes) don’t affect how the drug works.

Can a generic drug be less effective than the brand-name version?

No, if it meets FDA bioequivalence standards. The 90% confidence interval for absorption (Cmax and AUC) must fall entirely within 80-125%. This ensures that even with normal variations between individuals, the generic will deliver the same therapeutic effect. Millions of patients use generics safely every day.

Why do some people say generics don’t work as well?

Some people notice differences in pill size, color, or taste, and mistakenly think the medicine is different. Others may experience side effects due to changes in inactive ingredients, which are rare but possible. In very few cases, switching between different generic versions (from different manufacturers) can cause minor fluctuations in how a drug is absorbed-especially with narrow therapeutic index drugs. But this isn’t because the drug is ineffective; it’s because switching between products can disrupt stable blood levels. Your doctor can help manage this.

How long does it take for the FDA to approve a generic drug?

The standard review time for an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) is 10 to 12 months. About 65% of applications get approved on the first try. Many delays happen because of incomplete bioequivalence data or formulation issues. Manufacturers often need to reformulate or retest before resubmitting.

Are all generic drugs tested on humans?

Most are, especially for drugs meant to be absorbed into the bloodstream. These tests use 24-36 healthy volunteers in controlled crossover studies. But for drugs that act locally-like nasal sprays, topical creams, or eye drops-the FDA may accept lab-based (in vitro) testing instead, since systemic absorption isn’t the goal.

What happens if a generic drug fails bioequivalence testing?

The FDA issues a deficiency letter explaining why the study didn’t meet standards. The manufacturer must fix the issue-often by changing the formulation, improving manufacturing consistency, or running a new study-and resubmit. Only after passing all requirements will the drug be approved.

Is the 80-125% range too wide for safety?

No. The range is based on decades of clinical data and statistical analysis. A 20% variation in absorption is considered clinically insignificant for most drugs. The requirement that the entire 90% confidence interval must stay within 80-125% adds a strong safety buffer. For drugs where even small changes matter-like anticoagulants-the FDA applies stricter monitoring, not tighter limits, because the standard has proven safe.

8 Comments

Astha JainJanuary 19, 2026 AT 15:39

ok so like... bioequivalence? sounds like corporate jargon for "we made it cheap but still kinda works" lol. i mean, i’ve taken generics and sometimes they just... dont vibe with me? maybe it’s the fillers? or my soul? idk. but 80-125%? that’s like saying your ex is still "emotionally available" if they text you back 3 hours late. 🤷♀️

Erwin KodiatJanuary 20, 2026 AT 22:42

This is actually one of the most reassuring things about the FDA. People freak out about generics like they’re some shady back-alley deal, but the science here is rock solid. I’ve been on generics for years-blood pressure med, antidepressant, you name it. No issues. The 80-125% range? That’s not a loophole-it’s a buffer for human biology. We’re not machines. Bodies vary. The system accounts for that. Respect the process.

Lydia H.January 22, 2026 AT 02:03

It’s wild how much fear is rooted in ignorance. We’ll pay $200 for a brand-name pill because it looks fancy, but the generic? It’s the same molecule, same mechanism, same science-just without the marketing budget. I think about this every time I buy a generic. It’s not just savings-it’s justice. People in rural towns, seniors on fixed incomes, families choosing between meds and groceries-they’re the ones who benefit most from this system. The FDA didn’t cut corners. They cut the bullshit.

Jake RudinJanuary 23, 2026 AT 11:37

Let’s be clear: the 80–125% range is not arbitrary-it’s statistically derived from decades of pharmacokinetic data, validated through thousands of crossover trials, and peer-reviewed in journals such as AAPS PharmSciTech and the Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. Moreover, the 90% confidence interval requirement ensures that the probability of a clinically significant deviation is less than 10%, which is well within acceptable safety margins for non-narrow-therapeutic-index drugs. And yes-this is why the Hatch-Waxman Act was revolutionary. It didn’t lower standards. It eliminated redundant testing. Smart regulation, not cheap shortcuts.

Josh KennaJanuary 25, 2026 AT 00:56

Someone above said "my soul doesn’t vibe" with generics? Bro. Your soul isn’t a pharmacokinetic model. If you feel different after switching, it’s probably the damn dye or filler-not the active ingredient. I had a patient cry because her generic Xanax looked different. She thought it was fake. I showed her the FDA’s database. She was stunned. The system works. Stop letting Big Pharma scare you into paying extra for placebo branding.

Valerie DeLoachJanuary 25, 2026 AT 14:55

I’ve been a pharmacist for 18 years, and I’ve seen patients switch from brand to generic and back again-sometimes multiple times-because of misinformation. The truth? The FDA’s bioequivalence standards are among the most rigorous in the world. For narrow therapeutic index drugs like levothyroxine, we monitor levels closely, but that’s because of the drug’s sensitivity, not because generics are unreliable. In fact, the most consistent results I’ve seen? From generics. Why? Because manufacturers optimize for consistency to pass the test. Brand names? They’re allowed to vary more between batches. The system isn’t broken-it’s brilliant.

Christi SteinbeckJanuary 26, 2026 AT 02:37

Let’s stop pretending this is about medicine. It’s about money. And the fact that 90% of prescriptions are generics? That’s a win. Not for Big Pharma. Not for insurance companies. For YOU. For your grandma. For your kid who needs ADHD meds but can’t afford the brand. This isn’t "good enough." It’s perfect. The science proves it. The data proves it. The lives saved by affordable meds? That’s the real bottom line. Stop doubting. Start saving.

Jacob HillJanuary 27, 2026 AT 21:04

Just wanted to add: I work in a lab that does bioequivalence testing. We run these studies every week. The process is brutal. One batch fails because the coating dissolved 0.7 seconds too slow? Rejected. One volunteer had a weird gut reaction? Data gets tossed. The FDA doesn’t cut corners-they’re the reason you can trust that little white pill. I’ve seen companies spend millions re-formulating just to pass. It’s not easy. But it’s worth it. Because someone’s life depends on it.